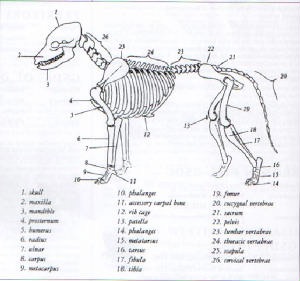

To assess soundness of construction and movement, it is important to understand the ‘bits’ that make up the dog. Every dog has the same type and number of bones (apart from length of tail) but the relative lengths of the bones give the great variation of appearance to the breeds. There are ideal proportions written down for each breed (the ‘standard’), but the basic bone structure is similar. Ideal proportions for each breed usually relate to two main areas:- 1. height (at the wither) to length (from the point of the chest or prosternum to the rear edge of the pelvis or ischium) and 2. depth of chest (wither to the lower edge of the chest) to length of leg (usually measured from the point of the elbow to the ground). The proportions combined with the angulations that are ideal for the breed combine to produce the characteristic movement of the breed.

Think of the dog as a system of levers and pulleys. The back acts as a bridge connecting the front and rear assemblies. If the ratio of the lengths of the bones of the front and rear are even, then the dog is balanced for that breed. The ideal lengths vary between breeds, but the principle always holds.

When trying to justify why relative lengths of different bones give better movement than others, one can go quite insane if you try to fit all breeds of dog to the one ideal. Having bred German Shepherds, my idea of an ideal construction is very different to someone with a toy dog or a Greyhound. The best way to look at dog construction is through function. What is the function of the breed, what is the characteristic movement for that breed and so on.

Movement and construction by function

To try to group different construction and movement ‘styles’, I would divide dogs into three broad categories:-

1. The walking or strutting dog, e.g. Fox Terrier.

2. The trotting dog, e.g. the German Shepherd.

3. The galloping dog, e.g. the Greyhound.

All the breeds range between these three types depending on size, function and individual breed selection characteristics eg. Such as the need to work in muddy conditions in the Belgian Shepherds, others are required to be exceptionally flexible and nimble eg the Kelpie.

Type 1 – the walking or strutting breeds. These breeds have a short bouncy action, where quite often the forequarter assembly is steep, they often have short backs with a reasonable turn of hindquarter for agility. The pasterns are often short and upright, usually asking for short tight feet. An example of this is the Fox Terrier.

Type 2 – the trotting breeds. These breeds are used where a tireless, and preferably economical trotting action is called for. Many of the working breeds fit into this category, with differences mostly in the forequarter where added nimbleness is asked for, eg. the Collie breeds, which are lighter boned and more open in angulation than the German Shepherd. The Shepherd is not being asked to be especially nimble, rather a tireless worker at its natural gait, the trot. The ideal German Shepherd dog is one that covers the maximum amount of ground with the minimum amount of effort, ie. fewer steps, translating to good reach and drive. Pasterns are longer and more sloping, giving better spring or flexibility, feet toe length medium to short, preferably with tight ligaments.

Type 3 – the galloping breeds. These breeds are used where great turns of speed are needed. This type is mostly found in the hunting dogs, particularly in the sight hounds e.g. Greyhounds. Here the maximum amount of thrust comes from longer, very powerful and well muscled hindquarters which push the dog up and stretch well forwards with very mobile, muscular shoulders, and very flexible pasterns. The feet have medium to long toes with “flatter” but still very flexible toes.

Forequarter Angulation and Movement

This is made up of several major components, being placement of shoulder, height at the wither, relative lengths of the shoulder blade, upper arm, foreleg and pastern – these all combine to determine the length of reach of the dog. The effectiveness of the reach will ultimately also be affected by the chest formation (which can alter with maturity), the strength and effectiveness of the hindquarter drive as it is transmitted up and forward along the back. With good balance of angulation, both reach and drive should be equally effective.

Reach

Length of reach of the forequarter assembly is determined by the lay of the shoulder blade, the relative lengths of the scapula (shoulder blade) and the humerus (upper arm), the length of foreleg, and the ‘arc of movement’ that the foreleg moves through.

Placement of Shoulder Blade

The definitions or terms used in this area are:

Well laid back – with the prosternum prominent (ie. visible in front of the point of shoulder when viewed from the side), which allows for maximum arc of movement from the top of the shoulder blade.

Upright (steep) – lacking prosternum – level with the point of shoulder or not visible when viewed from the side. The effect on movement at the trot is one of loose elbows (or lack of support by the chest) when seen coming towards one.

The wither is the area along the top of the shoulder blades, which obviously in turn relates to the placement of the shoulder. Most breeds call for a prominent or well developed wither – which can have a different meaning between breeds. When viewing the dog from the side, the withers should be higher than the middle of the back (in most breeds – lower in the OESD).

The height of wither is determined by how high the top of the shoulder blades are relative to the top of the dorsal spines of the vertebrae of the back.

High withers – the tops of the shoulder blades are higher than the top of the dorsal spines – this obviously gives the tightest muscling over the top of the shoulder blades (as there are shorter muscles), in turn giving firmer movement throughout the forequarter. Seen from the side the wither is higher than the middle of the back

Level withers – where the top of the dorsal vertebrae are level with the top of the dorsal spines. This gives more room for movement over the withers, allowing the shoulder to drop slightly in movement. Viewed from the side the wither is level with the back.

Flat withers (low) – the top of the shoulder blades are lower than the top of the dorsal spines. This allows a large degree of laxity during movement, generally causing falling on the forequarter. Viewed from the side the wither is lower than the middle of the back.

** If there is balanced movement, the wither should remain slightly above the line of the back during movement, hence the term “maintained a good (or high) wither at all speeds while gaiting”

Forequarter angulation

Diagrams of the good and the ugly.

- Very good forequarter angulation, with a maximum shoulder angle of 90’ ie. very good lay back of shoulder and very good length and lay of upper arm. This gives maximum length and reach.

- Most commonly seen shoulder angulation of 105’, with reasonable lay of shoulder and good length of upper arm, but slightly steep in placement – typical of a trotting breed. Good to very good reach.

-

Good layback of shoulder blade, but short steep upper arm, giving a restricted reach. Angle 120’. With a short steep upper arm, one is more likely to see a rather hackneyed gait in front.

-

Steeper placement of shoulder, but good length of upper arm. 120’ angle is typical of galloping breeds, slightly restricted in reach during the walk, but at the trot or gallop, the shoulder blade top moves backwards allowing for greater reach.

**In summary, the longer the upper arm (humerus), the better the reach, regardless of the length and lay of the shoulder blade.

Pasterns.

The pasterns act as the cushioning device for the load on the front legs during movement.

Short, upright pasterns have a reduced flexibility, and are commonly seen in the terrier breeds and those where a short bouncy action is called for.

Good medium length and angle of pastern (15’-20’) will allow great spring and flexibility of the pastern, reflected in a smoother gait as seen in the German Shepherd and the sight hounds.

Too long in pastern or too great an angle in relation to the foreleg, will result in loss of spring, over extension of the ligaments and a looseness (paddling effect) when viewed from front-on during movement. If severe, the dog will fall on the forehand.

Length of body – this is made up of several sections, and if correctly measured, is done so from the front of the prosternum to the end of the pelvis (the ischium). It is made up of the rib cage, the loin and the width of the hindquarter.

Rib cage – this area is from the prosternum in the front to the back of the ribs. It protects the heart and lungs, as well as the liver and stomach more caudally. Along the top of the rib cage is considered the true “back” and this extends from the wither to the loin. {*Many people when describing the back do so from the wither to the croup, or conversely, refer to the “backline or “topline” as a unit from the wither to the base of tail.}

Good length of rib – is considered a virtue in most breeds, allowing for greater lung room and endurance. “Well ribbed back” is a term used to highlight a good length of rib. Too short a rib cage – is generally considered undesirable as is too excessive a tuck up (“herring gutted”)

Spring of rib Most breeds ask for a good spring of rib, so as to allow for maximum lung expansion when needed, but other breeds may deem it attractive to be barrel ribbed, eg. the British Bulldog, and some go for the deep narrow chest, eg. the Borzoi.

The spring of rib when viewed from the front will affect the stance of the dog (see diagrams below).

The chest- generally refers to the forward section of the rib cage and must be looked at both from the front to see spring of rib and the side to see the depth – generally it should reach to the elbows when viewed from the side. If the chest is too shallow (side view) or too narrow (when view from the front), both result with insufficient support for the elbows, and looseness of elbows will result. Forward placement of the shoulders will similarly result in insufficient support for the elbows during movement.

Chests will with maturity, “drop” and broaden, and the elbows will become firmer. Too much chest development can result in excessive depth of chest relative to height and this will start to cause restrictions in reach and reduction in endurance. This can be seen more commonly in bitches after one or two litters. Narrow deep chested dogs have a higher risk of being affected by bloat as they get older.

From the side, the placement of shoulder relative to the chest becomes more obvious. Well laid back shoulder blade will generally have a good (more prominent) prosternum. Forward placed or steep shoulder blades have very little or no prosternum visible from the side view.

Stance in front (average breeds) – Diagrams

1. Correct – the legs drop straight to the ground. Elbows close to the sides of the chest, should move with tight elbows.

2. Barrel ribbed – too wide – wide front movement – elbows out, feet in, paddling effect, ‘loose at elbows’ and/or “out at elbow”

3. Slab sided – stands too narrow, elbows in, feet out (“east west”), looseness of elbow. Shallow chested dogs are similarly affected.

Back

The back is an area which many people overlook as it seems to be so obvious that it connects the back end to the front. The back is, in effect, a bridge between the two halves of the dog, and the strongest bridge has a slight rise over its apex. The ideal back is firm in movement. Movement of the back will cause loss of forward drive.

The length of back can also affect movement. If it is too short, the movement is restricted, and the dog is unable to drive properly; if it is too long, there will be bounce and loss of drive (see section on coupling).

The overall “backline” or “topline” where one is referring to the outline from the wither to the tail base can be greatly affected by the strength of ligamentation as well as the relative lengths of the back, loin and croup.

Roached backs – **If the middle of the back is arching up higher than the wither during movement, this is termed a roached back and is incorrect in most breeds.

Some breeds, notably GSD’s can be quite strongly ligamented over the back when young, and while standing may have a “roached” appearance. Additionally, many handlers unfortunately create this impression by setting puppies up in exaggerated stances. During movement, most of this rise should disappear. This effect should settle by 12-24 months, and while a firm back during movement is desirable, excessive roaching during movement even in the younger classes is not desirable.

As dogs age (particularly over 6 years of age), the ligaments stretch, loose some firmness, and the back transmission will suffer.

The loin. – this refers to the section from the end of the rib cage to the wing of the pelvis and consists of the lumber vertebrae. Most standards call for well developed muscling in this area, which generally should translate in movement to firm ligaments over this section of the backline.

There is considerable variation between breeds as to what is considered ideal length. The length of loin or “the coupling” is what creates most of the impression of length of body when considering the height to length proportions of a dog. Forward placed or steep shoulders can also give an impression of greater length of body.

Dogs which are too short in the coupling cannot extend properly while gaiting. Tall well angulated dogs that are short coupled cannot get their hindquarters under themselves sufficiently to drive effectively from their hocks. Most of the thrust of movement goes upwards, not forwards. Dogs which are too long in the coupling dissipate much of the forward drive along the back, particularly if the ligaments of the back are soft. The result is a back which bounces during movement.

1. Good length of coupling – the drive is transmitted with minimal loss along the back (providing the ligamentation is good).

2. Too short in coupling, can if well angulated result in a restriction of reach and drive, as much of the drive is transmitted up and over the back. If this is combined with a low or level wither, the effect seen is “falling on the forehand” – a desired trait in the OESD.

3. Too long in the coupling, where the drive is lost in the centre of the back due to the length, causing a bouncing movement. If combined with soft ligaments, the effect can produce a “swamp” or “dip back”.

Croup

The croup is the area from where the “wing” or front edge of the pelvis starts to the base of the tail. The length and angle of the croup affects the eventual width of thigh as seen from the side. While there are only small relative variations in the actual length of pelvis’ within a breed (bar a small variation for male versus female), the angle of the croup and the set of tail can very definitely visually alter the length seen when judging.

The angle of the croup affects the angle at which the hindquarter functions. Some believe that the croup has little effect, but most agree that too short and steep a croup, results in loss of hindquarter drive through an upwards rather than forwards motion. Ideally, a croup should be of good length and laid at a gentle angle to the back so that the drive up through the hindquarter flows forwards along the back without a break. A croup that is too short and in particular, too steep will considerably reduce the arc of movement that is possible from the hindquarter, resulting in restrictions in drive.

1. At 40’- too steep, where the angle of drive is too high, causing the back to rise during movement. Restricted in rear swing of the hindquarter due to the steep croup.

2. At 22’- croup good, the angle of drive is not too steep, where the thrust is forwards along the back. Good swing of the hindquarter (both forwards and backwards) is allowed by the croup.

3. At 10’ – croup too flat, angle of drive is lower than the back, and considerable thrust is lost as it is not transmitted forwards. The forward reach of the hindquarter is slightly restricted.

The angle of the croup should ideally flow in smooth line from the backline, allowing for maximum transmission of drive along the back. The ideal angle of the croup would be between 20’-30’ (from the line of the back). This variation is needed to allow for differences in lengths of backs and croups. The stronger back would probably tend to the 30’, whereas the longer back would tend to the 20’. The steeper the angle of the croup, the more it will affect the forward motion of the drive or hindquarter thrust.

The angle of the croup can change with age – young dogs with strong (dare we say slightly roached backs) may be rather steep in the croup, as the back settles down, so the angle of the croup may improve (seen around 12-24 months).

Hindquarter angulation and movement.

As with the forequarter, the relative lengths and angles of the croup, upper and lower thigh and the length of hock with greatly affect the drive and its effectiveness.

Correct hindquarter angulation must be seen relative to what is desired in the breed, relative to its characteristic movement. This is best be assessed from the side when the hind leg is positioned so that the hock is perpendicular to the ground.

The ideal angulation is one where the length of the femur is equal to the length of tibia/fibula (lower thigh). The longer both the femur and tibia/fibula are, the greater the turn of stifle for that breed. A quick way to check for equal lengths of femur and tibia is to raise the hock (perpendicularly, of course) up to the end of the pelvis. If the point of the hock extends beyond the rear edge of the pelvis, then the tibia is too long in relation to the femur. Rarely if ever is the femur too long.

Over angulation. This occurs when the length of the lower thigh is too long in the relation to the length of femur or upper thigh. This results in the hock (when perpendicular) being placed considerably further behind a line dropped behind the pelvis than when the lengths are equal. (The term over angulation also occasionally applies to those breeds with well-turned stifles, eg. the German Shepherd.)

The longer the lower thigh is in relation to the length of femur, the greater the amount of turn of stifle. The longer the hock in combination with a longer lower thigh, the more unstable the hock during movement. Shorter hocks will give greater stability, particularly where there is a longer lower thigh.

1. Short femur, long lower thigh, long hock.

2. Short femur, long lower thigh, short hock.

3. Short femur, longer lower thigh, where the point of the hock is behind the end of the pelvis when raised perpendicular from the ground.

Insufficient angulation (straight stifled). This is desired in some breeds, excessively so in the Chow Chow. It is, however, not a good direction to follow due to the increasing instability of the knee as the leg becomes straighter, placing more and more stress on the knee during exercise.

The knee is the major pivotal joint of the hindquarters and it takes all the strain of braking and twisting. Hock problems can be present as they become very upright, and will occasionally even bend forwards (‘double jointed’).

Hindquarter too steep, eg. the Chow Chow – In a hindquarter lacking angulation, the hock when perpendicular does not extend behind the end of the pelvis.

Stifle

The knee (or stifle joint). This is (from side to side) not as stable as is the human knee which is a lot wider. Due to this narrowness and in conjunction with a straight stifle (lack of good turn at the knee), the knee cap (the patella) can become unstable, and patella luxation may occur. Patella luxation is when the knee cap ‘jumps’ out of its groove and the dog cannot bear proper weight on the leg. This condition is considered genetic in origin, particularly so in toy breeds, but can also develop after accidents involving the ligaments of the knee. If the patella groove is deep, then patella luxation is less likely to occur.

The relative instability of a straighter stifle can cause the larger breeds to be more prone to damaging the anterior cruciate ligament – like a human football injury. This type of injury is not however, totally confined to those dogs with straighter stifles. It can occur in any hyperactive dog.

Due to the abnormal stance from a straight stifle, problems associated from excessive wear of the cartilages of both the hocks and knees can occur in the heavier breeds, particularly Rottweilers. This condition is often associated with overweight young dogs.

Hocks.

Tightness and firmness of the hocks during movement is desirable. The stability of the hocks is related to the relative lengths of all three sections – the upper thigh (femur), lower thigh (tibia/fibula), and the hock. Too long a hock, particularly when accompanied by a long lower thigh, allows for considerable instability of the hindquarter drive. Some breeds may stand cow hocked due to more angulation of the hindquarter eg. German Shepherds, but during their natural gait (the trot), the hocks should be firm and remain upright.

Length of hock relative to end size in puppies. Long hocks tend to go with increased size of the adult dog and a straighter hindquarter. Shorter hocks are more desirable in most breeds as they often go with better turn of stifle and greater firmness of hocks, therefore better transmission of drive. (*This is well worth noticing when purchasing a puppy, particularly in breeds with a top size limit of adults.)

Balance andTransmission

Balance – With balanced angulation both front and rear, and moving with a firm back; a dog of moderately good construction can generally out move a dog with just a good front, or just a good rear end. Ideally both fore and hindquarter angulation and construction should be such that the reach and drive are of equal power and effectiveness – inbalance will result in restrictions and a failure to maintain an even flowing gait.

Transmission is the force generated from the hindquarter thrust (or drive), which transmits along the back pushing the forequarter forward. The forequarter movement is more of a reaching, grabbing movement; and the hindquarter thrust allows maximum use of the forequarter construction.

If the back and the croup are good, then the transmission of the drive from the hindquarter through the back into the forequarter, will be transmitted smoothly and without loss of power.

If the back is too soft or too long and then the transmission forward is somewhat dissipated and the overall picture is one of a reduced ‘flow’, ie. the back will bounce around losing much of its power. Dogs with backs that are too short or too roached are similarly affected by a reduced transmission of power.

If there is good hindquarter construction and poor forequarter construction, the hindquarter drive tends to overrun the forequarter and so create the impression of ‘running down hill’ or falling on the forehand. The transmission is up through the back, then down, ie. a pounding effect, as the drive is excessive in relation to what the front can achieve.

If there is good forequarter construction and poor hindquarter construction, the hindquarter drive is insufficient to move the forequarter properly and consequently movement is restricted both front and rear and the hocks do not reach under the dog to achieve a good drive.

With balanced fore and hindquarter angulation, with good proportions and firm ligaments, the well constructed dog should approach the ideal movement for that breed.

A well constructed dog that has balanced movement is a joy to watch, the reach and drive are equally effective, and the dog seems to flow effortlessly around the ring with minimal effort and maximum ground cover. Unfortunately, it can be a rare event as well!!!